|

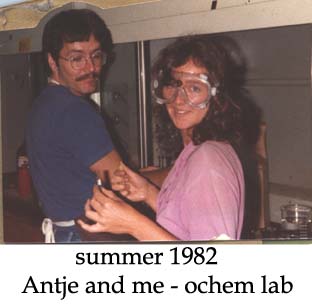

In the early afternoon of July 16, 1983, I was in the best condition of my life, riding my

In the early afternoon of July 16, 1983, I was in the best condition of my life, riding my

bicycle 25 - 50 miles a day, majoring in Biology at the University of California Santa Cruz (UCSC) and climbing Washinton Column,

in Yosemite, to celebrate my 28th birthday. Ron, Diane and I had hiked into the base of the column Saturday morning. His wife

watched us as we laid out the rope, climbing hardware and runners. Ron and I munched energy bars and discussed the upcoming climb.

"Climbing," I stated as I began moving upwards. At one point I stopped and threw down to Ron a tarp that had been left on a ledge. It fell

past him, down twenty feet, to the foot of the wall.

Although an accomplished climber of boulders, I had never lead climbed a big wall.

Hardware placement and rope management is essential. We were using chocks,wedges of metal that are very secure when placed in a crack

and pulled on downwards, but not so secure when pulled to the side. The chocks were to protect the lead climber (me) if I should

happen to fall.

"Climbing," I stated as I began moving upwards. At one point I stopped and threw down to Ron a tarp that had been left on a ledge. It fell

past him, down twenty feet, to the foot of the wall.

Although an accomplished climber of boulders, I had never lead climbed a big wall.

Hardware placement and rope management is essential. We were using chocks,wedges of metal that are very secure when placed in a crack

and pulled on downwards, but not so secure when pulled to the side. The chocks were to protect the lead climber (me) if I should

happen to fall.

To avoid the rope zig-zagging from chock to chock, runners are used. These are loops of one inch flat rope webbing, ten to twenty

feet long. By using runners the rope remains vertical and, if it pulls on a chock, it is in a downward direction. It is the lead climber's

responsibility to place and properly fasten the rope to each chock.

To avoid the rope zig-zagging from chock to chock, runners are used. These are loops of one inch flat rope webbing, ten to twenty

feet long. By using runners the rope remains vertical and, if it pulls on a chock, it is in a downward direction. It is the lead climber's

responsibility to place and properly fasten the rope to each chock.

I was involvedin an intense personal drama and wasn't really focused on seriousness of the matter at hand. After thirty minutes I began

moving too the right onto some very smooth treacherous granite, climbing for the ledge at its top, when I slipped. I fell past

the top-most piece of protection, the rope grew taut, every chock underneath was yanked sideways and pulled out and, then, the top chock pulled out too.

I was involvedin an intense personal drama and wasn't really focused on seriousness of the matter at hand. After thirty minutes I began

moving too the right onto some very smooth treacherous granite, climbing for the ledge at its top, when I slipped. I fell past

the top-most piece of protection, the rope grew taut, every chock underneath was yanked sideways and pulled out and, then, the top chock pulled out too.

My awarness was of being in a bad situation that was getting worse with every second. I slid and fell down the wall. I was one hundred and twenty feet above Ron when I slipped.

I was twenty feet below him when I stopped. There was a flash of white-hot pain and I passed out (for six weeks). Ron franticly untied himself and

hurriedly climbed down to me. He said I looked

like a deer that had been hit by a car. There was blood pouring out of my nose and mouth and my eyes were open, but there was

dust on them. He pulled the tarp, I had thrown down, over me and waited for rescue. Ron told me that I was barely breathing, the slight

movement of my chest indicating that I hadn't been killedby the fall.

My awarness was of being in a bad situation that was getting worse with every second. I slid and fell down the wall. I was one hundred and twenty feet above Ron when I slipped.

I was twenty feet below him when I stopped. There was a flash of white-hot pain and I passed out (for six weeks). Ron franticly untied himself and

hurriedly climbed down to me. He said I looked

like a deer that had been hit by a car. There was blood pouring out of my nose and mouth and my eyes were open, but there was

dust on them. He pulled the tarp, I had thrown down, over me and waited for rescue. Ron told me that I was barely breathing, the slight

movement of my chest indicating that I hadn't been killedby the fall.

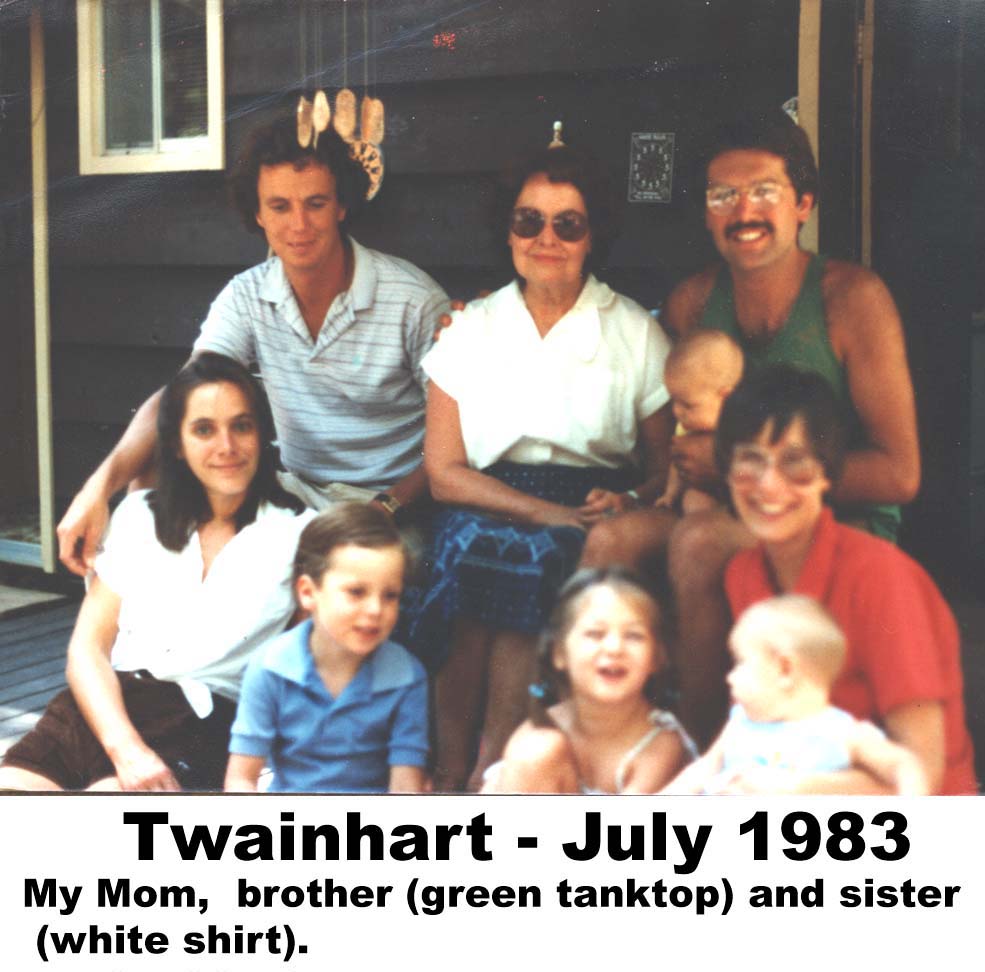

I was in a coma (which

lasted 6 weeks) with a broken back, broken left arm, four broken ribs, a punctured lung

and a traumatic brain injury (cerebral hematoma). My family gathered at Twain Harte. Everyone assumed I was going to die. The attending

physcian at the hospital I was flown to in Modesto advising my Mom to think about funeral arrangements.

I was in a coma (which

lasted 6 weeks) with a broken back, broken left arm, four broken ribs, a punctured lung

and a traumatic brain injury (cerebral hematoma). My family gathered at Twain Harte. Everyone assumed I was going to die. The attending

physcian at the hospital I was flown to in Modesto advising my Mom to think about funeral arrangements.

My mom retired from school teaching in March of 1983 and less then 6 months later

this happened. In the emergencyroom,

Dr. Howard told her that he had seen a number of patients with head injuries, none of whom was hurt as badly

as I was.

None of them survived, and it was his experience, I would not, either.

Mom was very upset by his prognosis,

it appeared she was about to bury her favorite child.

Mom managed to call my Aunt, Geneve, who immediately packed her car and drove 350 miles (arriving in Merced at 3 AM)

to be with her. Geneve later told me that

Mom was so hysterical,

she didn't sleep for three days.

My mom retired from school teaching in March of 1983 and less then 6 months later

this happened. In the emergencyroom,

Dr. Howard told her that he had seen a number of patients with head injuries, none of whom was hurt as badly

as I was.

None of them survived, and it was his experience, I would not, either.

Mom was very upset by his prognosis,

it appeared she was about to bury her favorite child.

Mom managed to call my Aunt, Geneve, who immediately packed her car and drove 350 miles (arriving in Merced at 3 AM)

to be with her. Geneve later told me that

Mom was so hysterical,

she didn't sleep for three days.

After nine months in three hospitals (the food at the third was terrible), I returned to UCSC for fall quarter

of 1984. I was introduced to necessity of using a wheelchair to ambulate. My fine motor

coordination on my right side was really messed up from the brain injury (my speech, balance, writing speed,

focusing - everything that required coordination between the two sides of my brain). My girlfiend told me I

sounded like "The Godfather". While my accident severely slowed my academic progress, it did not

prevent me from changing my major to Biochemistry and graduating

with that degree in March 1989.

After nine months in three hospitals (the food at the third was terrible), I returned to UCSC for fall quarter

of 1984. I was introduced to necessity of using a wheelchair to ambulate. My fine motor

coordination on my right side was really messed up from the brain injury (my speech, balance, writing speed,

focusing - everything that required coordination between the two sides of my brain). My girlfiend told me I

sounded like "The Godfather". While my accident severely slowed my academic progress, it did not

prevent me from changing my major to Biochemistry and graduating

with that degree in March 1989.

Getting my degree is easily the most difficult thing I have ever

done. Being disabled is not fun, but the poor quality of the people recruited to be lab assistants

and note takers is/was truly astounding.

I was unaware that such a caliber of student

would think themselve good enough to be a lab assistant, but no one else offered their services. It is/was my understanding

the competence of the students recruited is/was irrelevant. Disabled Student Services was having to get who ever they could

and it was immaterial that the disabled student they were assisting was being denied access to a quality education.

Getting my degree is easily the most difficult thing I have ever

done. Being disabled is not fun, but the poor quality of the people recruited to be lab assistants

and note takers is/was truly astounding.

I was unaware that such a caliber of student

would think themselve good enough to be a lab assistant, but no one else offered their services. It is/was my understanding

the competence of the students recruited is/was irrelevant. Disabled Student Services was having to get who ever they could

and it was immaterial that the disabled student they were assisting was being denied access to a quality education.

I was writing about six times slower then before I became

disabled. What this meant was that a homework assignment that was expected to take fifteen hours would take me ninety hours - and that was

for one class. This is what my poor writing skills meant: For example; my friends would go to movies or get together and socialize,

but I couldn’t join them because I was working on my homework to the best of my abilities (I never was physically able to complete

an assignment, despite the fact that I understood and retained the material presented in class). I spent hours and hours alone,

working on the homework, doing my best, realizing how poor my efforts really were; feeling despondent, hopeless and horrible. I needed help writing. My

self-image suffered terribly and has never recovered.

I was writing about six times slower then before I became

disabled. What this meant was that a homework assignment that was expected to take fifteen hours would take me ninety hours - and that was

for one class. This is what my poor writing skills meant: For example; my friends would go to movies or get together and socialize,

but I couldn’t join them because I was working on my homework to the best of my abilities (I never was physically able to complete

an assignment, despite the fact that I understood and retained the material presented in class). I spent hours and hours alone,

working on the homework, doing my best, realizing how poor my efforts really were; feeling despondent, hopeless and horrible. I needed help writing. My

self-image suffered terribly and has never recovered.

|